“Diversity may be the hardest thing for a society to live with, and perhaps the most dangerous thing for a society to live without.”

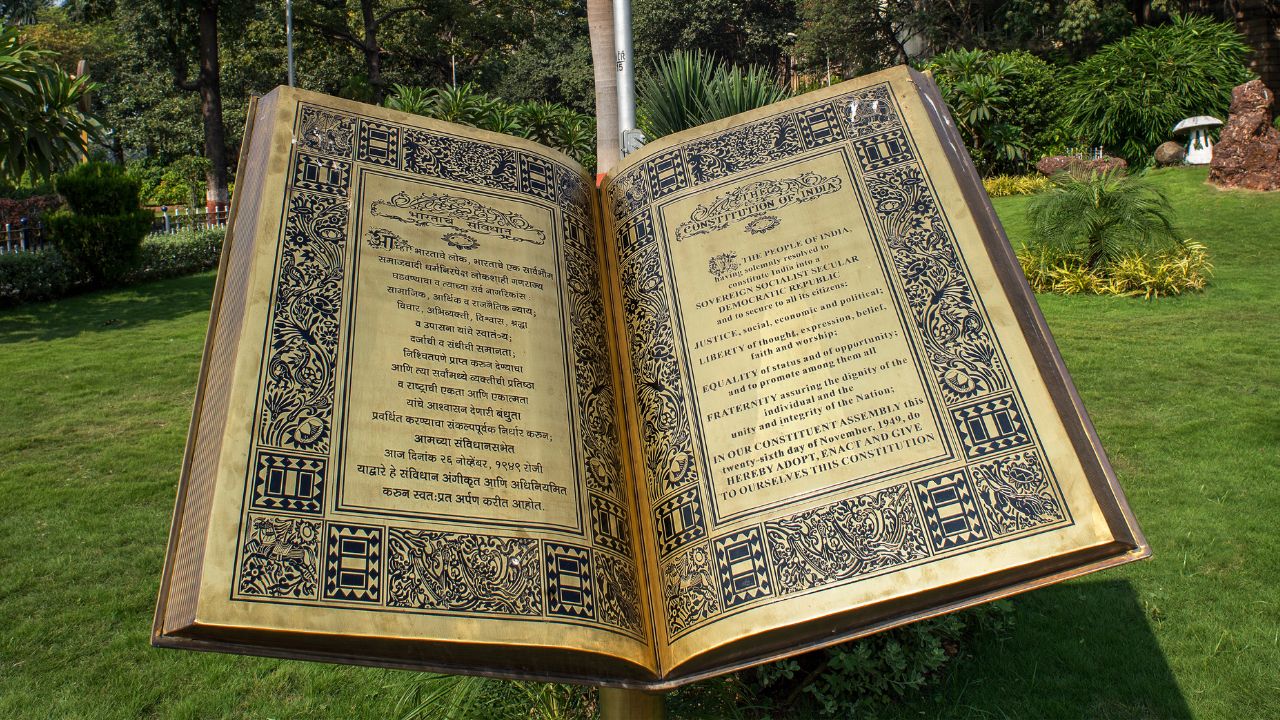

The current debate over the need for a uniform civil code concerning all matters of marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption and succession has divided the nation. The UCC is documented under Article 44 of the constitution as an aspirational goal as the constituent assembly couldn’t come to a general consensus at that time, considering the fabric of the nation was fragile, and they couldn’t risk alienating communities at a time when they needed fervent national unity.

The first part of our series will document the colonial roots of the Uniform Civil Code and how they apply to the current political debate. Considering the Hindu, Muslim and other personal laws deal with topics involving marriage and succession around which every religion has its own rules and regulations derived from their sacred texts. When discussing UCC its important to note there are countless multiplicities to be involved and considered when an all-encompassing law such as this is to be made.

The great debate:

The framers fiercely debated the need for a uniform civil code. Some of the fiercest defenders of the personal laws were inevitably Muslim—who were anxious about their status in the aftermath of the Partition. Leaders argued that in the case of Muslims, the personal law was closely linked to the freedom of religion:

I would like to say that any party, political or communal, has no right to interfere in the personal law of any group. More particularly I say this regarding Muslims. There are three fundamentals in their personal law, namely, religion, language, and culture which have not been ordained by human agency. Their personal law regarding divorce, marriage, and inheritance has been derived from the Quran and its interpretation is recorded therein. If there is any one, who thinks that he can interfere in the personal law of the Muslims, then I would say to him that the result will be very harmful.

Supporters were liberal nationalists who viewed the personal laws as a threat to a unified Indian identity—which was still fragile and newborn. Also: a UCC was essential to ensure the equality of women:

Member K.M. Munshi however, rejected the notion that a UCC would be against the freedom of religion as the Constitution allowed the government to make laws covering secular activities related to religious practices if they were intended for social reform. He advocated for the UCC, stating benefits such as promoting the unity of the nation and equality for women. He said that if personal laws of inheritance, succession and so on were seen as a part of religion, then many discriminatory practices of the Hindu personal law against women could not be eliminated.

Before discussing arguments that are in favour of or against the uniform civil code it’s important to note the intense complexity of even creating a draft bill that can be submitted to be reviewed in the Lok Sabha monsoon session. Currently the Uttarakhand state government has taken it upon themselves to draft a UCC. Justice Desai, who is heading the UCC committee formed by the state, also confirmed that the draft of the Uniform Civil Code is ready and is at a printing stage after which it will be submitted to the state government.

The Many Problems That Will Need To Be Addressed:

The Hindu personal law is broken into three segments The Hindu Marriage Bill, Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Bill and Hindu Succession Bill. There are also various exceptions to these laws in different states that need to be taken into account. The Muslim Personal Law, previously considered archaic and patriarchal, also underwent significant reform after the landmark Shah Bano Case. With as many irregularities as exist in a pluralistic country like ours, it’s essential to ask ourselves if it’s better to amend the personal law instead of forcing the entire nation under one law considering how closely these laws are tied to religious sentiments across all religions of our country.

To explain the complexity, let’s take the example of Conjugal Rights:

There are certain rights which the husband and wives have which can be demanded. These are known as conjugal rights. According to Section 99 of the Hindu marriage act, if any of the spouses deserts the other along with his/her society without any probable cause or justification, the aggrieved party can file a case in court and seek restitution of conjugal rights. There is no such mention in the Shariat application act regarding this. So, what will be the stand of the proposed Uniform Civil Code on this?

End Remarks:

The concept of one nation, one law sounds good on paper. Still, in order to implement it, the UCC should presumably incorporate the most modern and progressive aspects of all existing personal laws while discarding those which are retrograde. The UCC concept is Western and might not even apply to a country like ours, whose beauty comes from its diversity. If a law passed intending to bring, national unity becomes the very reason for a nation to break apart and harbour resentment among its citizens, is it really worth it?

– Harsha Chhawchharia (Editorial)